The Reptile

Sometimes it’s a tough business living in the modern world. Test cricket isn’t what it was, you can’t smoke in pubs, and there’s no good shops to browse in when you have a few minutes to kill in town. You also have expectations of your horror movies that people in the old days did not; like when things happen at night, for example, you expect it to be dark.

Clearly the same cannot be said for your sixties movie goer, judging by The Reptile. As long as there were enough frogs croaking on the soundtrack, apparently they were perfectly happy with night looking like day. It almost sounds like one of those old sayings - ‘No matter that the sky is light, frogs in Cornwall equals night’. The thing is, I’m not sure when noisy West Country amphibians became synonymous with nighttime, but it’s safe to say the decision has been reversed since. An attitude of - who needs darkness when you have a old record with frogs on it - no longer cuts the mustard.

It’s difficult to argue, because atmosphere is pretty bloody important in a horror movie. Some bloke wandering the moors in daylight is just not as scary as someone walking over them at night. I have done both, as it happens, and when I did it during the day it was absolutely delightful, and when I did it at night I was scared out of my tiny mind.

Now when The Reptile goes inside, that’s when it comes into its own, because it can use shadows (a.k.a. darkness) to properly scare you just by having a monster appear suddenly. I really jumped when it did too, because it was a spooky old house with lots of corners (again, dark) where anything could be hidden. And when it turns out that what’s hidden (because of the darkness) is a hungry snake monster, well then, we are watching a proper horror film and good on them for making it.

However, the other thing your modern movie watcher expects from their horror film is a reason for the damn thing to be happening - and look, it doesn’t have to be an allegory about family, or regret, or flipping global warming - It can be as simple as bloke done wrong, bloke now monster. It doesn’t have to be clever clever but it does need to make sense. So when the story of The Reptile turns out to be: chap goes to faraway land (cool), winds up a secretive religion (got it), is cursed by said snake worshipping cult (excellent, as he should be), a curse that turns his daughter into a half-snake, half-woman monster (the patriarchy avoiding direct responsibility again) and so... one of the cult’s priests goes to England to live with the father and daughter in some kind of mad sitcom set-up? Eh? It seemed to me on first viewing that the whole film was happening because this priest was a rum foreigner and therefore up-to-no-good, and that was reason enough for him to be setting a monster loose upon the population of Cornwall. Unfortunately, I need a little more to enjoy my horror movie than: The Reptile is coming for you! Because... Foreigners! Perhaps the modern world has spoiled me with its backstories and internal narrative logic, but I can’t help that can I?

Sadly, your modern viewer also has expectations that a horror film should end with an exciting climax; one that comes about as a direct result of the story’s events. So in The Reptile, when you hear that the snake-woman hates the cold, hates it!, you think ‘Oh-ho! I can see this monster being forced out onto the cold moor, or falling into an icy lake, or something of that nature!’ This is the pact between film and audience: You tell me the monster’s weakness and I’ll happily wait for it to be dispatched in a poetically appropriate way at the very end of the movie. In other words, a blooming climax. But in The Reptile, somebody breaks a window to get into the house and in the process lets in a bit of a draft. And then the snake woman says ‘Oh no! Some cold!’ and falls down dead. This, in my humble opinion, does NOT constitute a climax, I don’t care how much of the set you’ve lit on fire. Especially if the set is supposed to be a cave, and therefore stone, and therefore not flammable.

Now, all of this is a great shame, because there are things that were much better for audiences back then. They didn’t need absolutely everyone in a movie to be young and beautiful for a start. And so the best thing in The Reptile, by a country mile, is that Michael Ripper gets a juicy part. The perpetual pub landlord gets a chance to shine and he’s absolutely brilliant. After years of polishing glasses and refusing to tell anyone anything about any castle if you don’t mind, he comes out from behind the bar and helps take down the monster with a mixture of courage and practical good humour that makes you think the blokes in the pubs in Hammer could have done so much over the years if they’d only had the gumption.

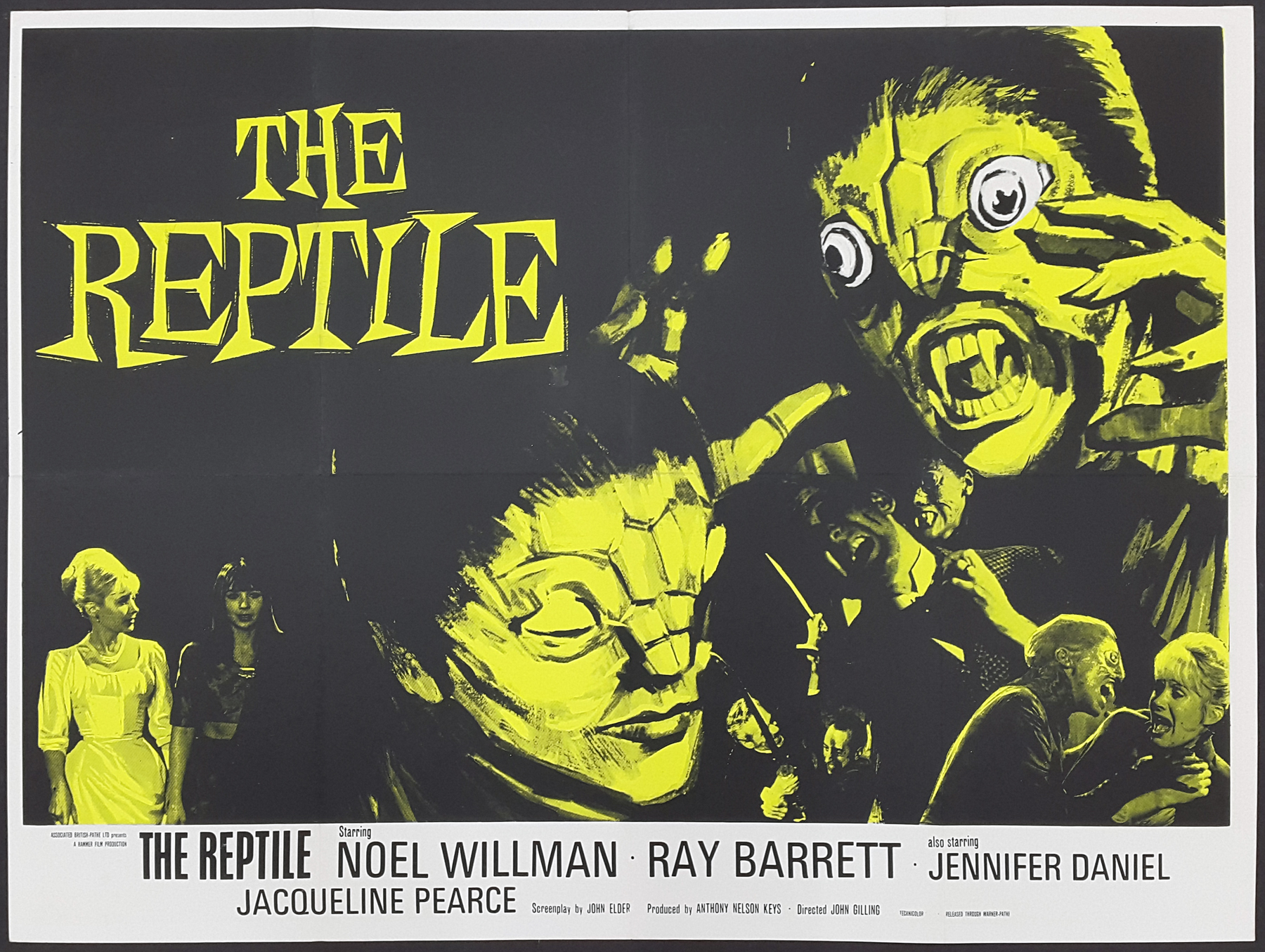

The monster is pretty good too! This is no CGI phantom without weight or presence, it’s a poor young woman with a snake’s face. And, alright, it isn’t the greatest make-up in the world, but it does look like a woman with a snake face, which is what she is after all, and that alone is pretty scary and also pretty sad - exactly how it should be! And there are great locations too, with graveyards and tumbledown cottages, and big spooky mansions; the sort of places that are so scary because they’re real and not just a studio set.

All the things that make Hammer uniquely brilliant are here, it’s just there’s too much that, as a resident of the modern world, I find it very hard to see past. I wish I could quite honestly. I’d rather remain ignorant of the downsides of something, and just enjoy myself quite frankly.

Speaking of which, another pint?

If you enjoy The Bloke Down The Pub reviews, why not check out the author’s book Are you hurtling towards God knows what?